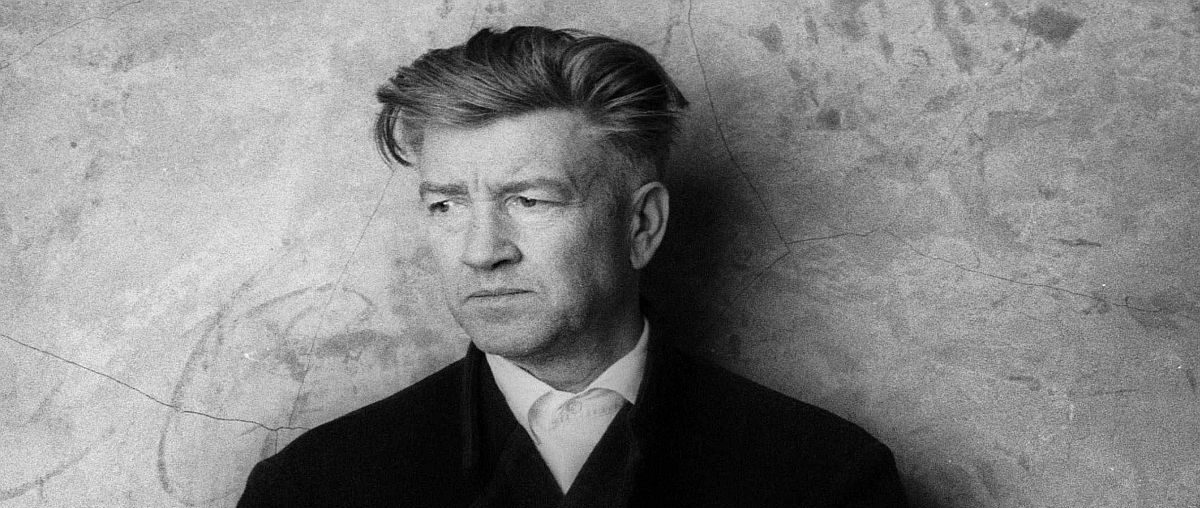

In Memoriam: David Lynch

One year ago, the world lost David Lynch, a visionary whose work reshaped our understanding of what cinema and television could be. His death marked the end of a remarkable artistic career that spanned nearly five decades, but his films and series continue to speak with undiminished power. Lynch never condescended to his audience nor compromised his vision for easy answers. He trusted us to embrace ambiguity, to feel rather than decipher, to accept that some mysteries deepen rather than resolve.

What made Lynch extraordinary wasn’t just his distinctive aesthetic, the industrial soundscapes, the disrupted surfaces of everyday life, the dreamlike logic – but his fundamental generosity as an artist. He invited us into worlds that challenged and unsettled us, yet always with profound humanity beneath the strangeness. Whether exploring the darkness under suburban lawns or the consciousness of a woman losing herself, Lynch approached his subjects with curiosity and compassion. In remembering him, we return to his work not as relics but as living experiences that continue to reveal new dimensions with each encounter.

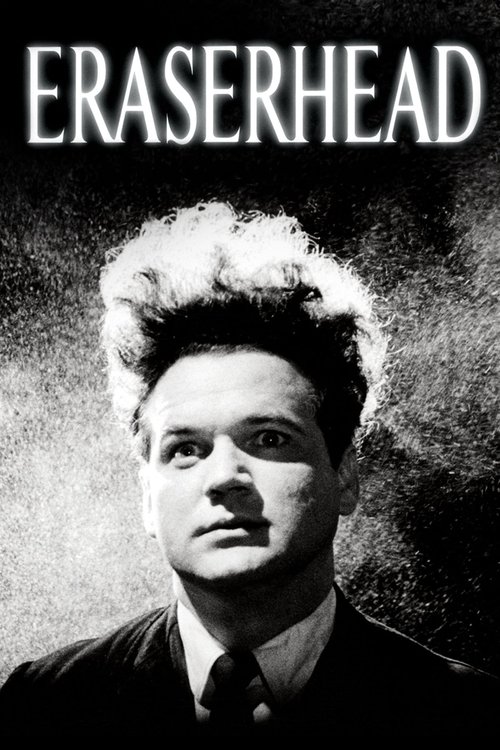

Eraserhead (1977)

Lynch’s debut remains a seminal experimental film in American cinema. Eraserhead is a nightmarish plunge into industrial dread, paternal anxiety, and the surreal logic of dreams. Its gloomy black-and-white imagery and dissonant sound design create a world that feels alien and ominous. The film resists interpretation in a way that became quintessentially Lynchian, inviting viewers to sit with discomfort rather than decode it. Even decades later, its visceral strangeness and emotional rawness remain unmatched. It’s the work of an artist announcing himself boldly, without compromise.

The Elephant Man (1980)

Lynch’s sophomore feature represents a notable departure from his debut, a classically structured drama that still carries his unmistakable sensibility. The Elephant Man tells the story of Joseph Merrick with compassion rather than spectacle. Lynch balances darkness against tenderness, revealing how cruelty and kindness can inhabit the same heart. The film’s restraint is part of its power. It never feels manipulative, only profoundly empathetic. It proved Lynch could work within a studio system without losing his voice, and it remains one of his most moving works.

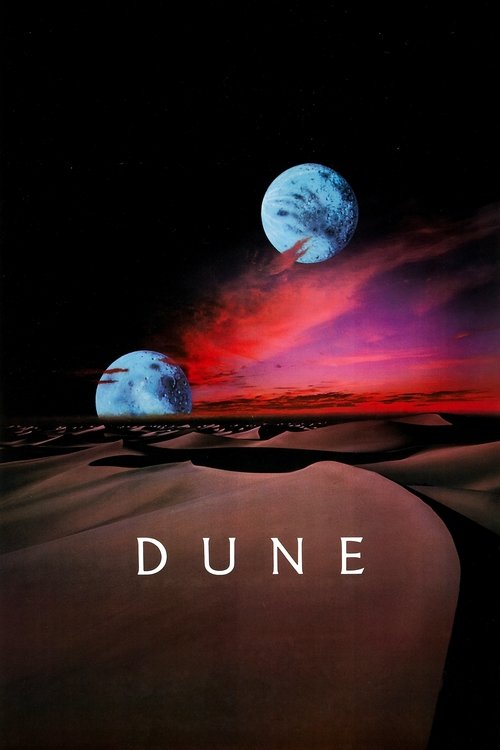

Dune (1984)

Lynch’s Dune is an ambitious adaptation that bears the marks of both grand vision and studio interference. The film’s dense mythology, ornate production design, and bursts of surreal imagery hint at what Lynch might have achieved with full creative control. While uneven in places, it’s also filled with moments of beauty and unmistakable allure. Over time, it has achieved a cult following, not as a faithful rendering of Frank Herbert’s novel but as a glimpse into an alternate cinematic universe where Lynchian sci-fi might have flourished. Its imperfections fade beside the evocative, enduring beauty it leaves behind.

Blue Velvet (1986)

Blue Velvet is the film that solidified Lynch’s reputation as a director unafraid to explore the darkness beneath everyday life. It begins with the idyllic surface of small-town America and then peels it back to reveal rot, desire, and violence simmering underneath. The contrast between the bright, nostalgic exterior and the hellish underworld creates a highly-charged tension. Lynch’s control of tone is masterful. He is darkly humorous one moment, then plunging us straight into the bruised, decadent underbelly lurking beneath a veneer of innocence the next. The performances, especially from Isabella Rossellini and Dennis Hopper, push into raw emotional territory. It’s a film that reshaped American independent cinema and remains one of Lynch’s most influential achievements.

Wild at Heart (1990)

A feverish road movie drenched in pop-culture references and melodrama, Wild at Heart is Lynch at his most playful. The film follows two lovers on the run, but the plot is really a vehicle for a barrage of stylized violence, dark humor, and surreal detours. Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern bring a charismatic focus to the story, grounding its excesses with genuine feeling. The film’s energy is deliberately off-the-rails, but beneath the madness lies a sincere belief in love as a defiant force. A work of unfiltered passion.

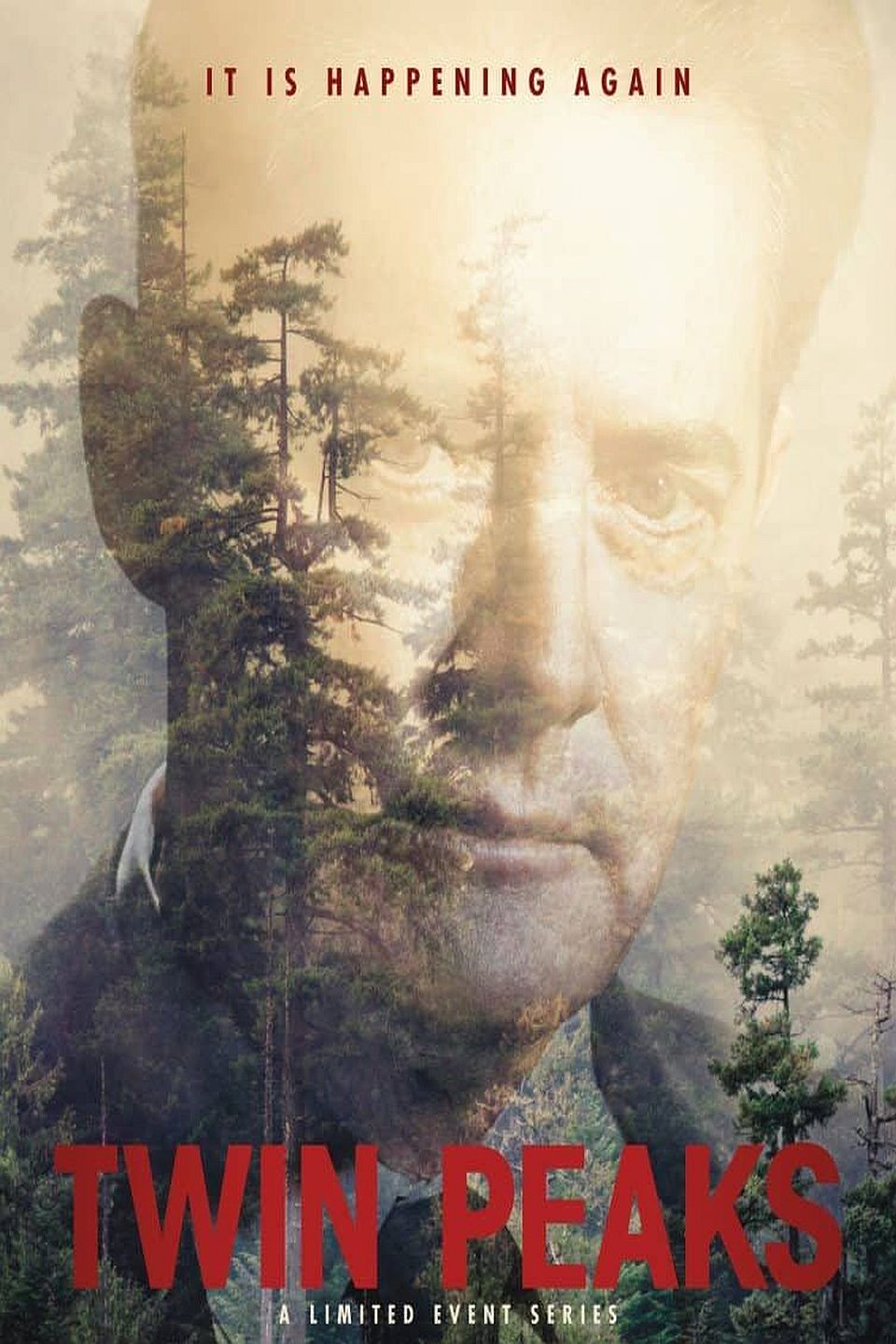

Twin Peaks (1990-1991)

Twin Peaks shattered television’s boundaries by proving the medium could sustain cinematic ambition and surreal storytelling. What began as a murder mystery evolved into something stranger and more profound; a meditation on duality, hidden darkness, and the permeable border between dreams and waking life. Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost populated their Pacific Northwest town with characters who felt simultaneously archetypal and deeply human. The show’s tonal shifts from genuine warmth to cosmic horror created a viewing experience unlike anything before it. Though network interference led to an uneven second season, Twin Peaks‘ influence on prestige television remains incalculable. It proved viewers would follow something different if delivered with sincerity and artistic vision.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992)

Initially dismissed, Fire Walk with Me has since been recognized as one of Lynch’s most devastating works. Rather than offering closure to the TV series, the film dives into the final days of Laura Palmer’s life with unflinching emotional intensity. It abandons the quirky charm of the show for something darker, more intimate, and spiritually harrowing. Sheryl Lee’s performance is extraordinary, giving Laura a voice and presence the series only hinted at. The film’s dream sequences and supernatural elements deepen the mythology, but its core is a portrait of trauma rendered with compassion and raw intensity.

Lost Highway (1997)

Lynch plunges into pure psychological disorientation with this unsettling nightmare. The film unfolds like a Möbius strip, looping identities, timelines, and realities into a hypnotic puzzle. Its neo-noir elements of smoky clubs and ominous highways create a sense of dread that never dissipates. The narrative doesn’t so much progress as fold back on itself, trapping viewers in a maze where cause and effect become meaningless. What emerges is less a mystery to solve than an atmosphere to endure, one thick with paranoia, desire, and the terror of a self coming undone. Lynch abandons linear storytelling entirely, trusting image and sound to convey what dialogue cannot. It’s a film that operates on dream logic, where transformation happens without explanation and identity becomes fluid. For many, it marks the beginning of Lynch’s most uncompromising phase.

The Straight Story (1999)

Perhaps the most surprising film in Lynch’s career, The Straight Story is a gentle, quietly profound tale based on a real Midwestern journey. Richard Farnsworth delivers a beautifully understated performance as Alvin Straight, who travels hundreds of miles on a lawnmower to reconcile with his brother. Lynch approaches the material with sincerity, finding poetry in rural landscapes and everyday encounters. The film’s simplicity is its strength, revealing Lynch’s deep affection for ordinary people and the rhythms of American life. It’s a reminder that his artistry isn’t limited to the jarring and surreal. He could do tender, too. While Harry Dean Stanton appears only briefly as Lyle, Alvin’s brother, his natural authenticity brings a deep poignancy to the conclusion of the film.

Mulholland Drive (2001)

Often hailed as Lynch’s masterpiece, Mulholland Drive is a dream that slowly turns into a nightmare. What begins as a seemingly straightforward Hollywood mystery dissolves into a fractured exploration of identity, desire, and the illusions of the film industry. Lynch’s control of atmosphere is extraordinary. Every scene feels charged with either possibility or apprehension. Naomi Watts delivers a career-defining performance, navigating the film’s emotional and structural transitions with fidelity and skill. The movie obfuscates definitive interpretation, yet its emotional impact is unmistakable. It’s a haunting, seductive vision of Los Angeles as a city where both dreams and nightmares are born.

Inland Empire (2006)

Lynch’s most experimental feature, Inland Empire, is a disorienting journey into the psyche of an actress losing her sense of self. Shot on early digital video, the film has a raw texture that mirrors its disjunctive narrative form. Scenes bleed one into another like half-remembered dreams, creating a sense of unease that’s exhausting yet mesmerizing. Laura Dern’s performance shows a character moving through chaos, terror, vulnerability, and ultimately arriving at transcendence. The film demands patience, but it rewards viewers with a uniquely immersive experience where Lynch pushes his art to its most abstract extremes.

Twin Peaks: The Return (2017)

Twenty-five years after the original series, Lynch returned with eighteen hours of the most audacious television ever broadcast.The Return abandons conventional narrative structure entirely, unfolding instead as a patient meditation on time, trauma, and the nature of evil. Lynch moves at his own pace, scenes stretch into uncomfortable lengths, familiar characters appear transformed or broken, and whole episodes abandon plot for atmosphere and experimentation. Kyle MacLachlan delivers multiple extraordinary performances as various iterations of Dale Cooper. The series demands total surrender to Lynch’s vision, rewarding trust with moments of devastating beauty and existential terror. It’s less a sequel than a culmination, Lynch synthesizing decades of artistic exploration into something that feels like a transmission from another dimension.

David Lynch left behind a body of work that refuses to become mere nostalgia. His films and series remain vital because they operate according to their own internal logic, speaking to something primal and true even when they defy rational explanation. He showed us that American life is full of contradictions – beauty and rot, innocence and depravity, the mundane and the transcendent, often occupying the same frame.

In the year since his passing, his influence has only become more apparent. We see traces of his uncompromising nature in filmmakers willing to embrace ambiguity, in television that treats audiences as collaborators rather than consumers, and in artists who trust their instincts over market testing. Lynch proved that strangeness and sincerity aren’t opposites but companions, that you could be both deeply weird and deeply gracious.

His work endures not despite its difficulty but because of it. These films and series ask us for our patience, our openness, and our willingness to surrender control. In return, they offer experiences that persist in the mind, just slightly out of reach, forever unresolved but somehow essential. Lynch’s gift was to invite us to embrace mystery, to find meaning in mood and image, and to accept that some questions matter more than their answers. His vision remains as eccentric, as challenging, and as necessary as ever.