Teorema (1968)

Teorema

An enigmatic visitor (Terence Stamp) inexplicably appears in Milan and into the lives of a wealthy bourgeois family. For a time, he lives with them in their estate. Each member of the household is drawn to him. The mother (Silvana Mangano), the father (Massimo Girotti), the son (Andrés José Cruz Soublette), the daughter (Anne Wiazemsky), and even the housemaid (Laura Betti) all have their own affairs with the visitor. And then, just as the volcanic ash blows to and fro on Mount Etna, the visitor suddenly announces during a family meal that he will be leaving the following day. His departure causes each member of the household to fall into states of despair and longing.

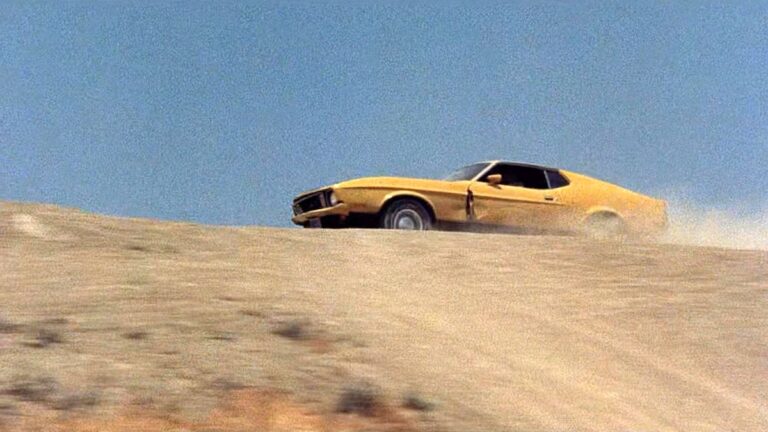

What follows is less a conventional narrative than a series of transformations. Pasolini uses the visitor’s presence to expose the fragile structures that hold the family together. The film’s recurring images of Mount Etna, with its drifting ash and stark terrain, mirror the emotional upheaval that overtakes each character. The volcano becomes a kind of silent witness, a reminder of forces older and more powerful than the comforts of modern life. Pasolini’s framing, his use of silence, and his refusal to explain the visitor’s origins all contribute to a sense of revelation that feels intimate and unnerving. The symbolism is never heavy‑handed, yet it subtly shapes the viewer’s understanding of the family’s unraveling.

Within Pasolini’s larger body of work, Teorema marks a moment when his interests in politics, spirituality, and social critique converge in a particularly distilled form. By the late 1960s, he had already established himself as a provocative voice in Italian culture, someone unafraid to confront the contradictions of his time. This work extends his exploration of the sacred within the everyday, but it does so by turning its gaze on the bourgeois world rather than the marginalized communities of his earlier films. It moves with a quiet confidence that invites contemplation. Pasolini strips away traditional storytelling and allows the imagery, performances, and stark compositional choices to carry the meaning. In doing so, he creates a film that resists easy interpretation yet remains deeply resonant, a kind of cinematic parable that invites reflection rather than offering clear answers.